#WomenEd Blogs

Exploring the label of ‘the angry black woman’

by Dr Valerie Daniel @Valerie_JKD

As a black professional woman I am in this intersectional space of being somewhat respected by my peers whilst still being marginalised within the wider society. I say ‘somewhat’ respected because my entire journey here in England from 1989 until now has been fraught with ‘you are too passionate’; ‘you are very sensitive’; ‘I don’t mean to be offensive or anything but.......’ and my personal favourite ‘You have a chip on your shoulder’.

I used to wear my hair in braids and was told by a well meaning white colleague that I presented as a ‘militant black woman’ which was a shock to me. As a larger black woman I was told by another well meaning white colleague, that my size was intimidating to a certain white TA who was extremely difficult in my class but chose to put in a complaint against me about my size! As if that was not bad enough, it was upheld as a case to be answered to without any evidence of me being anything but professional to this member of staff. I could carry on with numerous stories that allude to me being ‘an angry black woman’ culminating with actually being called ‘an angry black woman’ more than a couple of times over the past two weeks.

While looking for some deeper understanding of this intersectional space I find myself in, I spoke to my friend Dr Sharon Curtis who has written an article entitled ‘Black women’s intersectional complexities: The impact on leadership’. Sharon names certain identifying factors like black women’s accents, or choice of dress, traditional hairstyles like braids, afro or dreadlocks, alongside their personal values and religious beliefs that impact on them as leaders as these factors deviate from a prescriptive view of women as leaders as envisaged by a predominantly white culture. Cultural racism is based in the idea that some cultures are superior to others and that some cultures are basically incompatible and really should not exist in the same society. This is an added issue to biological racism that is rooted in the belief of biological superiority between ethnic groups. I grew up in a family of professionals in Jamaica where I was expected to succeed and excel.

I spent 29 years of my life in Jamaica before coming here and what was evident to me when I got here was that I seemed to consistently hit up against this unspoken but flagrant understanding of where a black woman’s place was supposed to be in society.

Therefore because I wouldn’t conform, I was perceived as ‘opinionated’ and actually referred to as ‘formidable’, again inferring that my capabilities plus my size somehow instilled fear in my white counterparts. This therefore, is a complex intersectional space for black women and it sits squarely within the concept of ‘intersectionality’ as coined in 1989 by Professor Kimberlé Crenshaw to describe how other individual characteristics including race, class and gender “intersect” with one another and overlap. ‘Intersectionality’ has become a concept that is used politically to polarise society on the lived experiences of black women. Those on the far right see ‘intersectionality’ as an attempt to place non-white people ‘on top’ and those on the left see it as minorities receiving special treatment. So either way black women are in a position where they can’t win. As Crenshaw succinctly puts it, intersectionality therefore either “promotes solipsism at the personal level” or “division at the social level.” So either way it is ‘really dangerous’ as it will upend racial and cultural hierarchies to create a new one where black people are in power or it is ‘a conspiracy theory of victimisation’. Although ‘intersectionality’ accurately describes the way black women encounter the world, there is an obvious resistance to demolishing racial hierarchies to create an equal and equitable society.

Background

We are currently living through a particularly rough time in race relations across the world. This has come about as a response to the death of George Floyd, a black man who died at the hands of the police in the USA in an exceptionally brutal and inhumane manner. This has galvanised a movement to highlight systemic racism in predominantly white countries as denoted by the worldwide ‘Black Lives Matter’ protests. The hostility that has arisen around these protests has been epic to say the least! There is a lot of anger on both sides of this issue and quite a bit of ‘mud-slinging’ in and amongst the voices of highly qualified, robustly informed, high profile black women who have been speaking out about their own experiences and broadening the narrative about black people and people of colour, with indisputable facts and statistics. However, what resonates with me is, despite open aggression on both sides of this issue and some really vile and vitriolic comments from white women and white men, the label of ‘angry black woman’ was frequently thrown at women who were using a reasoned and reasonable approach to protest and voice their righteous indignation at the inequality in society.

When I questioned this on social media the response was ‘Why can’t you be more like Hilary in the Fresh Prince of Belair’; Hilary is the personification of the stereotypical spoilt, white, rich girl with just a tiny bit more melanin in her skin. I suppose Hilary is a more acceptable version of a black woman.

The stereotype of ‘the angry black woman’

The ‘angry black woman’ is a trope that depicts all black women as loud, aggressive and prone to violence. I find it interesting that redheaded white women who are stereotyped as feisty are described as hot-tempered, hot-bloodied, hot-headed; invoking metaphors of heat and passion but never referred to as ‘the angry white woman’. Stereotypes are largely held as a somewhat fixed but oversimplified image of a type of person but in the case of black women this trope is weaponised “to silence and shame black women who dare to challenge social inequalities, complain about their circumstances, or demand fair treatment” (Harris-Perry, 2011). It was indeed shocking how increasingly unpleasant and foul-mouthed white men became when as a black woman I maintained my composure despite the attempts to bait me; ‘I suppose you are kissing your teeth now!’ When my response was ‘No because I’m not mad at you but I am really good at kissing my teeth’, this gentleman became really incensed. This prompted me to have a closer look at conversations between white men and black women in general on social media and I noticed that where women engaged in trading insults, this seemed to invite more accusations of the stereotype of ‘angry black woman’.

The aftermath of slavery and its resultant social, economic, and political effects have rendered black women as victims of negative stereotyping which has been described by Pilgrim (2015)as "a social control mechanism that is employed to punish black women who violate the societal norms that encourage them to be passive, servile, nonthreatening, and unseen" (p. 121).

Viola Davis, award winning actress for the TV series ‘How to get away with murder’ was quoted by “Entertainment Weekly” in 2015 as saying, "Toni Morrison said that as soon as a character of colour is introduced in a story imagination stops”. The black stereotypes seem to kick in at this

History

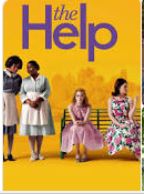

Viola is also famous for her role in the movie ‘The Help’ and the vivid image that is used to advertise the movie powerfully conveys subliminal messages about black women in society.

Imagine this image as a more equitable one and tell me what it would look like and what the subliminal message should convey.

Historically, black women have the burden of being classified in two minority groups: black and female. Interestingly enough one of my social media experiences over the last two weeks was of a white male who alluded to a ‘score card’ that black women could automatically tick against their skin colour and against their gender as victims, confirming the conspiracy theory of victimisation as posited by Kimberle Crenshaw. This man further stated that white men were the true victims as they did not have a score card to tick that allowed them to opt out of their responsibilities. It really was interesting having that vantage point expressed from the perspective of male, white privilege because as a black woman we usually perceive this ‘score card’ as the one that gets used to tick the ‘I am an equal opportunities employer ‘ box with the token black female employee which puts another spin on the victimisation conspiracy theory. Historically as well, black women who have been traditionally marginalised and dehumanised are seen as being void of normalised human emotions and incapable of real educational achievement. These concepts are produced and reproduced through black female invisibility from high-profile jobs and from elected office and being conspicuously absent by their invisibility in mass media. When they are catapulted into the public arena, the overt and subliminal messages range from the loud, ‘angry black woman’ behaving badly to the ‘afro-centric’ activist ‘angry black woman’ to the ‘tokenistic racial gatekeepers’ who are used to tick the ethnicity box but are placed in positions of influence to maintain the status quo. Refer to @ShuaibKhan26 who has written a blog entitled ‘A different shade of BAME’ which addresses ‘racialised gatekeepers’.

Conclusion

The space that black women occupy in society is a culmination of their experiences at the hands of not only white men but black men and white women as well. Their daily experiences of invisibility and dehumanization go largely unrecognised and are only usually picked up when these women are in a heightened emotional state in response to the pervasive micro-discrimination and micro-aggression that is their everyday life. The label of the ‘angry black woman’ puts black women in that place where they either have to embrace the stereotype or embrace their lives as second class citizens. As my experience demonstrated, black women are tarnished with this label even when they are calm, confident and composed and even when they use logic and context to unpick some hardened and unfair assumptions about them. This label is intended to silence black women and put them firmly back into their place with no recourse to challenge the inequality of their status or their place in life.

These are the consequences of speaking up about inequality: • Hyper-visibility and accusations of displaying threatening behaviour • Displaced blame which deflects attention from the aggressor and places blame squarely on the person being targeted • Accusations of receiving special treatment which negates their intelligence, their qualifications and their natural abilities. • Accusations of either having an inferiority complex or wanting power. • Accusations of reliance on public handouts, breaking down societal norms with one parent families, hyper-sexuality, drug use and any number of social ills which blames victims for their misfortunes. • Treated with suspicion or accused of living beyond their means if they acquire possessions with their hard earned money. • White women being seen as needing to be protected generally but the ‘angry black woman’ can fend for herself.

In 1851, Sojourner Truth, a black American abolitionist and Women’s Rights activist—disrupted a Women’s Rights Convention, when she spoke powerfully, plaintively asking “Ain’t I a Woman?” She advocated for women’s rights for black women in a time when black women were not allowed to speak up for themselves. Such is the courage of a woman who was fighting for her right to be equal.

This is a part of her famous speech: “That man over there says that women need to be helped into carriages, and lifted over ditches, and to have the best place everywhere. Nobody ever helps me into carriages, or over mud-puddles, or gives me any best place! And ain’t I a woman? Look at me! Look at my arm! I have ploughed and planted, and gathered into barns, and no man could head me! And ain’t I a woman? I could work as much and eat as much as a man––when I could get it––and bear the lash as well! And ain’t I a woman? I have borne thirteen children, and seen most all sold off to slavery, and when I cried out with my mother’s grief, none but Jesus heard me! And ain’t I a woman?”

So my question is what has changed from 1851 until now? We are all members of one human race yet society still perpetuates this shameful practice of relegating black woman to the bottom of the pile of society. Somebody is bound to point out the number of interracial relationships, but stop and have a conversation with these couples and listen to the abuse they regularly face especially on social media. Since there is no way around the label of ‘the angry black woman’, the way through it is, not to allow ourselves to be burdened or controlled by the label. Use the label to politely demand an equal place in society. Lastly I wish to say something a really close friend said to me this week. She said our plight may be a fact but it is not the truth. I leave you with a poem from Maya Angelou.

And still I rise

You may write me down in history

With your bitter, twisted lies,

You may tread me in the very dirt

But still, like dust, I'll rise.

Does my sassiness upset you?

Why are you beset with gloom? '

Cause I walk like I've got oil wells

pumping in my living room.

Just like moons and like suns,

With the certainty of tides, Just like hopes springing high,

Still I'll rise.

Did you want to see me broken?

Bowed head and lowered eyes?

Shoulders falling down like teardrops.

Weakened by my soulful cries.

Does my haughtiness offend you?

Don't you take it awful hard

'Cause I laugh like I've got gold mines

Diggin' in my own back yard.

You may shoot me with your words,

You may cut me with your eyes,

You may kill me with your hatefulness,

But still, like air, I'll rise.

Does my sexiness upset you?

Does it come as a surprise

that I dance like I've got diamonds

at the meeting of my thighs?

Out of the huts of history's shame

I rise

Up from a past that's rooted in pain

I rise

I'm a black ocean, leaping and wide,

Welling and swelling I bear in the tide.

Leaving behind nights of terror and fear

I rise

Into a daybreak that's wondrously clear

I rise

Bringing the gifts that my ancestors gave,

I am the dream and the hope of the slave.

I rise I rise I rise.

When you subscribe to the blog, we will send you an e-mail when there are new updates on the site so you wouldn't miss them.

Comments